Dressing up for the Arctic

My all time favorite question regarding my trips beyond the Arctic circle (and the one I get asked about the most) is – how do I dress for such weather?

People assume that venturing to Svalbard and Greenland with intention to be active outside requires gear similar to the one for walking on the moon – big, bulky, filled with all sorts of down or synthetic fibers with isolating qualities. They get very surprised when they hear that I cannot imagine using such gear, as my first criteria is having the ability to walk and move freely when I wear it. Anything that restricts my movement in any possible way is useless for me and is a hard pass. And I mean – Hard. Pass.

Second criteria is the ability to layer the gear up. There are several layers which work wonders for me, as they can be upgraded or removed as necessary, depending on the conditions.

Wool & cashmere

I own a lot of wool garments, skiing baselayers which go direct on my skin. Living in Norway implies that you have them in your wardrobe, they are unavoidable. They are not made of grindy and uncomfortable wool which itches in a way you’d lose your mind, these garments are incredibly soft and gentle and those who had no contact with it usually are left in shock when they hear what they hold in their hands.

Up until 2-3 years I considered myself too uncouth to wear fine garments made of cashmere. I am not a gentle person even a bit, and the basis for me owning anything is a “it’s a tool, not a jewel” principle. Meaning, I will not be a slave to an expensive garment, it is bought to be used and not treated like a snowflake on a palm. Until, of course, I tried and wore a cashmere sweater in Svalbard directly on my skin like a wool baselayer. Bought it (on sales, I am very thrifty) and realized it has OUTSTANDING technical capabilities. Worn directly on skin works like two wool baselayers at the same time. Now I own several of those, skin tight, with high collars – and they are wonderful to have when the winds start to blow the heat off of me.

This whole wool & cashmere story covers undergarments – baselayer shirts and tights. They are incredibly easy to find here in Scandinavia and I cannot imagine going out without them.

In any case, forget about cotton. It does not retain the warmth, it gets easily sweaty and once you cool down in your sweat when it’s -20 outside – you are screwed.

Fleece

I am not a fan of fleece because wool is more than enough for my warmth needs (and it also releases microplastic into the sea, which is just another minus) but I have a few pieces which serve as a backup layer, if the temps drop significantly and I decide to layer up. Fleece garments are going over the baselayers and significantly up the game.

Woolen sweaters

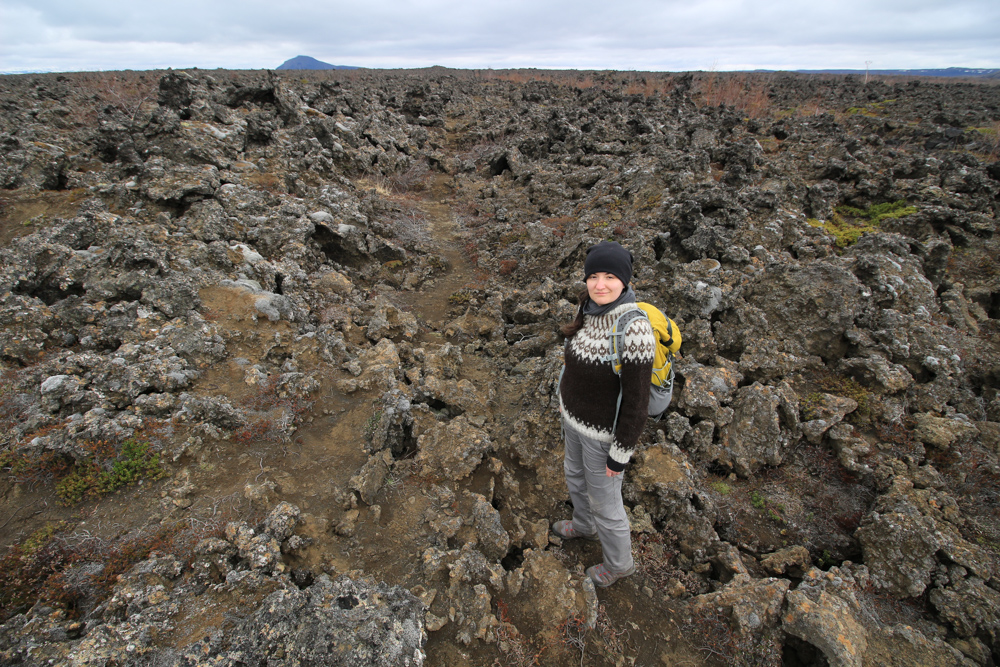

A better alternative to fleece is a good woolen sweater. The Scandinavians are the experts for making such garments and those gorgeous woolen goodies will probably outlive their owner’s grandchildren. I prefer to wear them instead of fleece because they are more breathable; I get warmed up extremely easily and while I am walking across the mountains. I even use those sweaters instead of shell jackets if it is not raining. They insulate excellently and I don’t break any sweat in them.

Technical outer layers

I have a lot of technical clothes, and if I need to, I can walk this second out of my house to the temperature up to probably -30C without buying anything first. By “technical clothes” I mean – waterproof and windproof synthetic shell trousers and jackets which are the first line of defense in demanding conditions.

The only garment I do not own but is related to these activities is a down (feather) filled jacket. For me, this is an extra extra layer which is really not necessary. It works amazingly well in activities when you are more or less passive, such as boat trips, when the temps drop.

Hats & scarves & gloves

Even in the coldest regions I did not need anything thicker than a relatively thin woolen beanie. When the weather turns, it is enough for me to pull the shell hoodie over the head.

I avoid scarves of almost all possible sorts; tube scarves made of wool, thin, soft and foldable work magic when it comes to being outside, they keep me warm properly and can fit under collars of any zip up garments I have in my wardrobe.

I am notorious for having almost no gloves and prefer to hike barehanded. Again, I am a very warm person and I take hundreds of photos and videos – I want my hands to be free in every possible second. I will occasionally put the hands in the pockets or use very thin woolen gloves (I am not even sure if they exist, which is the best possible quality for a garment which is being carried to a hike), if needed.

Hiking shoes

The only brand that I was ever loyal to was Salomon. I wore several of their good hiking shoes throughout the years and I was very happy with how comfortable they are, had a good shape and beautiful designs. A year and a half ago I switched to Alfa, a company which produces probably the best hiking shoes in the world, designed for Norway by Norwegians. Meaning, they work excellently in the Arctic, which is what I need.

Layering up, to sum up the whole story

Packing myself in gear is defined by the planned activity. It depends on my plan – will I hike or be more static (like on a boat tour)?

Even when the temps drop under zero, if there are no strong winds or heavy rain, I usually have only my wool baselayer and a good woolen sweater over it. During the hikes I start waking with an outer shell but it gets off five minutes after as I get heated up really fast.

This changes entirely when I go on the boat tours on whale spotting tours or to glide among the icebergs – then I layer up as much as I can, including a fleece layer – in order to stay warm. On such trips I avoid returning to the heated area on the boats, I want to absorb the rare beauty of the Arctic and will spend every possible second admiring it while being exposed to it.

I went on a boat trip a month ago. It was done in the late evening, in a small boat, among the enormous icebergs in Isfjorden near Ilulissat, Greenland.

It was cold; not unbearably, as I layered up massively, but we were sitting on the benches while the boat was scraping over ice chunks falling off these icebergs, the wind was blowing and you could almost taste the ice around you.

In conclusion – buying good technical clothes is a great investment in my book, because the North Atlantic region waits for me to walk on its shores, and the colder it is, the better. For me, going outside is a devout experience, almost ritualistic, and – like for the church – I want to look and feel my best when I am somewhere out there.