Sermeq kujalleq

Due to the current social, political and (oftentimes wannabe) scientific climate, there are many people who are seeing glaciers almost exclusively through the catastrophic global warming glasses. A lot of people, especially those who have any palpable profit from it, are screaming about the impact of a beef burger or a cotton t-shirt on the ice volume on our planet, aiming at the conscience of every single one of us and preservation of natural wonders. But, beyond this relentless noise lies a beauty, a rare one, which itself does not get a proper amount of attention for just being itself – the glaciers and the ice themselves. I am always asking myself, do those who try to protect them and are instigating the preservation are even able to understand how beautiful they are?

I am one of those people who always was and will be fascinated by natural occurrences in a very intense and personal way. I love ending up in the middle of a warm summer rainstorm. I enjoy being outside when the snowflakes are descending in chunks and will gladly venture out as soon as the snowstorm begins. Especially during the night. Cloudless starry skies for me are a spectacle to observe. They are even better in wintertime. Thundering skies are exceptionally beautiful to watch and I miss seeing them so much. I trained myself not to obsess over weather and have learned to find beauty in any possible weather scenario. You get the idea. This means that the possibility to observe and visit such nature’s forces as glaciers was incredibly interesting to me.

Pasterze

The first glacier / ice gateway drug I ever visited was Pasterze in Austria, on Großglockner Hochalpenstraße. We were on our way from Croatia to Norway on the motorcycle and one of the stops was the nearest glacier we could come near by. The idea of ice accumulating for hundreds of thousands of years, reaching even a few kilometers in thickness, partially rethawing and refreezing seasonally, flowing along the valley between mountains and ending up in the ocean was really intriguing.

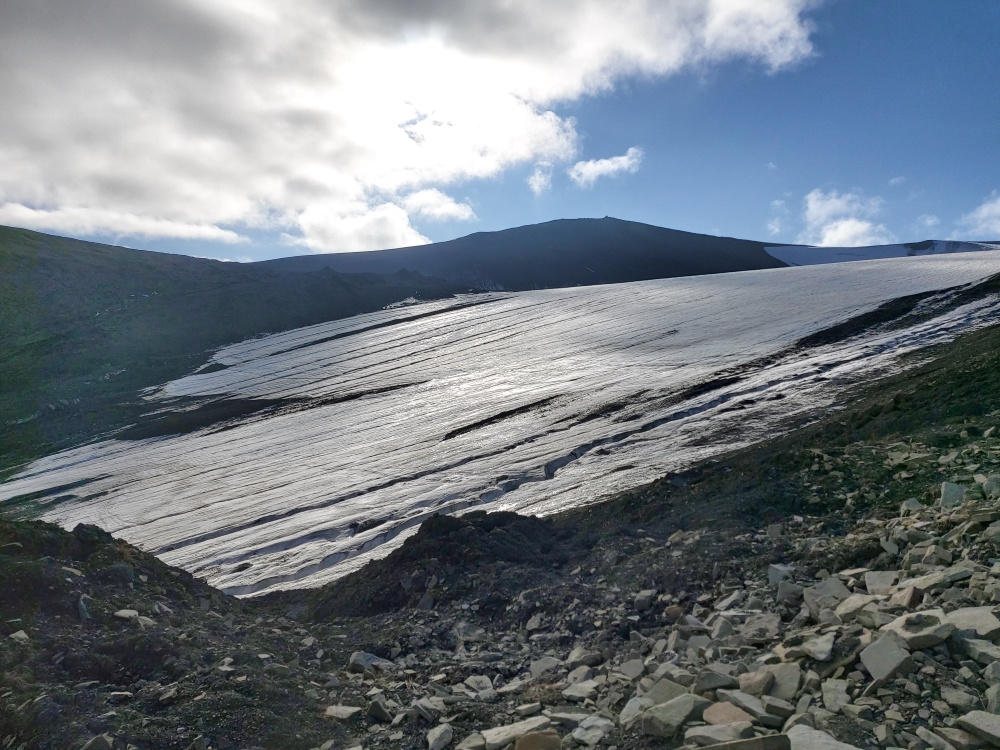

Imagine the older layers, which did not see the Sun for ages, and due to the pressure from the younger layers the air eked out and gradually turned from white color to different shades of blue, with numerous cracks and crevasses on the surface. What really makes the glaciers in general interesting is their activity. The glaciers always look so serene and silent, especially those who descend into the sea. In reality, they are very active and noisy – cracking, churning, groaning, calving and sliding enormous chunks of ice towards the sea or in valleys between the mountains.

So far, 12.

Guided by these ideas, I have visited several of them.

In Austria:

- Pasterze

In continental Norway:

- Svartisen

- Jostedalbreen

- Austerdalsbreen

In Svalbard:

- VonPostbreen

- Esmarkbreen

- Nordenskiöldsbreen

- Larsbreen

- Longyearbreen

- Grønnfjordbreen

- Foxfonna

Iceland:

- Fláajökull

On some of them I walked. Near some of them I just stood and stared, amazed. Oftentimes, you stand in front of an arm of a glacier, hundred meters high and feel tiny. What makes you even smaller is the glacier’s length measured in dozens of kilometers which you cannot see from your standpoint, often connecting with another glacier.

Each time I come close to a glacier I fall in love even more with them and I just cement and fortify the idea of visiting more of them and booking any possible related activity that I can when the opportunity arrives.

Sermeq kujalleq glacier

When I was deciding which entry city for Greenland will be on my first trip to the world’s largest island, the factor which made me pick Ilulissat was the glacier Sermeq kujalleq. Superficially, sounds like an irrelevant factor, but only if you do not know what it is.

Why is Sermeq kujalleq so special?

It is the most active and productive glacier of the entire northern hemisphere. On the global level it is surpassed only by Lambert’s glacier in Antarctica. It moves up to 50 m/day, meaning, releasing up to 50 meters of ice from the glacier belonging to Greenland ice cap to Isfjorden, the Icefjord in Ilulissat. It is estimated that 35 billions of tonnes of ice (6% of the ice cap ice) yearly calve off to the sea. The glacier itself is monstrously enormous, its width reaches 7 km and 65 km in length. If you want to see how it looks, there is a fantastic documentary called Chasing ice which shows the largest glacier calving event ever filmed.

I wanted to see the icebergs. Towering, enormous icebergs. Due to Sermeq kujalleq and its high activity, Ilulissat is the iceberg capital of the world. There is no better place to observe them and enjoy the view.

Heli-flight over Sermeq kujalleq

During my visit in Greenland, I booked a helicopter flight over Sermeq kujalleq, which included a ground stop of 30 min at the edge of it. The glacier itself is entirely inaccessible by any other means of transport – you cannot hike to this point or obviously use a boat. You can only fly to it. I was preparing myself mentally for this activity probably even more than a southern drag queen coming to a backstage meet and greet with Beyonce. Unfortunately, the excitement was shot down due to unforeseen circumstances; the heli-flight had to be canceled and I missed the top notch planned activity.

But I walked along Isfjorden on several tracks and trails and at least saw the icebergs belonging to it.

At the Isfjordcentret can a visual representation of the Sermeq kujalleq be found. Beautifully executed, I must say.

Ilulissat can be found on the left bottom end. What you are looking at is the throat of the glacier, through which the icebergs are passing to the Isfjorden.

I truly hope that I will have the chance to see it in person, from the sky.